Hair Me Out: Confronting cultural appropriation

In a new modern world where cornrows and box braids are the latest fashion week trend; the rich history and the importance these hairstyles have had, and still continue to have, in Black culture has been blurred by Coachella Instagram posts and popularised by the Kardashians.

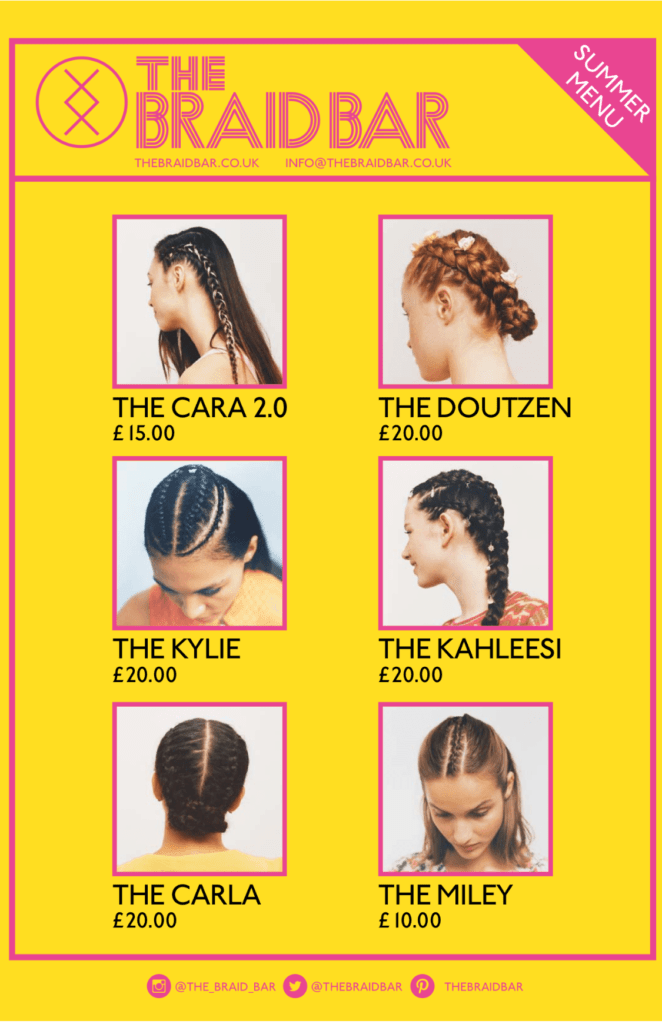

Black-owned hair salons that specialise in afro hairstyles have been completely overlooked, as rich celebrities (such as Cara Delevingne) take a journey to Selfridges to indulge in The Braid Bar. A costly hair salon that ‘specialises’ in braiding. Owned by two white women from West London, Sarah Hiscox and Willa Burton.

Sarah Wilcox claims that “there was nowhere in London that I could take her to get a quick

braid and not have to pay a fortune for it” (Selfridges Magazine, 2015). This level of

ignorance expands the gap in the beauty industry that does not recognise talented Black

hairdressers and Black talent, period. This is a recognised form of discrimination. Instead of taking her daughter to a Black-owned hair salon, she exercised her privilege as a middle-class, Caucasian women and created a make-belief afro hair experience. TikToker ‘@taversia’ defines cultural appropriation as when “someone takes a feature from a closed

culture, to which they do not belong, and then divorces it from its roots. And then, capitalises off of it, socially or financially”. This defines exactly what The Braid Bar exemplifies.

The importance of cornrows in Black history is not something to be dismissed. Braids

allowed captured Black people to store a few grains of rice within their strands, to have a

minuscular amount of food to barely suffice them in the cruellest of conditions. Intricate

patterns were braided into the afros of slaves seeking freedom, as maps for other slaves to navigate fields. The rich yet brutal history of braids in America and Britain is enough to

justify why it is not acceptable for white hairdressers to claim these styles as their own or as celebrities’. Nowadays, white hairdressers’ profit from cornrows by rebranding them as

‘Boxer Braids’ and ‘Boho Braids’. In the case of The Braid Bar, they have transformed this

and renamed braids after white celebrities, crediting them for the hairstyles.

The hairstyles displayed on their websites are named after celebrities such as ‘The Kendall’ (after Kendall Jenner) and ‘The Posty’ (after well-known rapper, Post Malone). With the public outcry of Kendall’s Pepsi advert, this namesake is in poor taste and a blatant display of ignorance. The advert itself shows that white people are not in a place to indulge in other cultures as police brutality and bigotry will not change by simply being ‘nice’ to an aggressive policeman, Post Malone has also been under fire for culture appropriation through his hairstyles and ‘blaccent’. The Braid Bar has further supported this notion by associating his persona with cornrows.

Famous Black celebrities such as Zendaya have been publicly humiliated for wearing their afro/curly hair in African/Caribbean hairstyles such as dreadlocks. Giuliana Rancic referred to Zendaya’s locs as “smelling like patchouli and weed”, reinforcing and encouraging negative stereotypes that have plagued Black lives for centuries. The Braid Bar was presented with an opportunity to give Black celebrities with Black hairstyles some positive recognition. Two strand twists are legendarily considered as a staple of Snoop Dogg’s persona, fashion, and career. Now, the Braid Bar does have a Snoop namesake, however, having a white model to portray such an infamous hairstyle is not exactly progressive. Beyoncé repopularised thin, straight cornrows, adding to the inspiration and popularity of afro hairstyles, adding to the recent Y2K fashion revival. The very beauty and history of afro and braided hair has been the subject of adoration and appreciation in Beyoncé’s visual albums ‘Lemonade’ and ‘Black is King’.

Historically, Black people have been stigmatised and called ‘unprofessional’ with braided hair and Beyoncé has notoriously been a pivotal attribute in changing this narrative. Black women such as Zendaya and Beyoncé should be given the opportunity to stimulate our

culture in a world-renowned store such as Selfridges. Throughout the ‘menu’ of services they provide, there is only one Black female model represented on the website. The model portrays a look named ‘The Naomi’, which feels as though they picked the first Black woman they could think of. Naomi Campbell is famously known for her sleek, straight locks and has only been documented in twists once, frankly, this feels ignorant and un-researched.

It appears that this was a backhanded attempt at filling in a diversity quota. The model’s hair has blatantly been relaxed and straightened to fit the theme the Braid Bar is embracing. It’s not uncommon for Black women to wear straight hair, however, haircare is of the upmost importance in Black communities. A silk press is the process of caring for afro hair whilst straightening it. This is done through deep hydration and a ‘one-pass’ technique to minimise the amount of heat exposed to the hair. Silk presses show how far Black communities have come in preserving their culture and hair care in the face of white oppression. The act of relaxing afro hair was one introduced for Black people to assimilate into white societies, to reduce the discrimination being thrown at Black people. On behalf of The Braid Bar, to have a Black model with relaxed hair is a massive step backwards. This begs the question of: if a Black person with natural hair walked into the Braid Bar, would they know what to do with

afro/curly hair?

Besides the lack of credit to Afrocentrism, The Braid Bar’s prices are highly extortionate, with the price of two braids (named ‘The Naomi’) priced at £30. In my own experience of going to afro hair salons, I have been charged £20 for two cornrows with extensions. The women that braid my hair have perfected their intricate craft due to their culture and history.

The prices that afro hair shops charge are not a reflection of the talent and labour that goes into braiding hair. The prices reflect what they know the people in their community can afford. These are the women that deserve spots to sell their talents in Selfridges, at Selfridges prices. But unlike Selfridges, Black hair shops do not just evolve around profit, they provide a communal familiarity that cannot be bought or mimicked in an imitated experience. Regarding the afro salon experience, what makes it so unique is the community. It’s usually a place of comfort where the community meets up to engage with each other on a personal level. Your hairdresser isn’t just a hairdresser in an afro hair shop. Essentially there is a family-fill that no one could get in Selfridges.

Whilst I am happy to see Black hairstyles become the norm and new root of fashion, it should not be considered as ‘newly created/discovered’ by people with European hair, credit should be given where it is due. The Braid Bar and Selfridges as a whole, have exploited and profited of the Black community and disguised it as progression. The steps to becoming culturally appreciative involve directly buying from the cultures you want to embrace.

Discover more from GUAP’s Fashion section here