The Pre-Raphaelite Renaissance: Fashion’s Use of Art to Address Racial Diversity

Words by Anna Chauri Phillips

November’s Google tribute to Victorian model Fanny Eaton illustrates a growing phenomenon in contemporary culture: the Pre-Raphaelite Renaissance.

2020 not only saw a burgeoning interest in Pre-Raphaelitism but a reworking of its ideas, with the fashion industry an active participant. From magazine shoots to new releases from Beyoncé herself, fashion is taking its lead from the mid-nineteenth-century avant-garde group of artists calling themselves the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood.

Appalled by the copious paintings at the Royal Academy idealising classical mythology, the Pre-Raphaelites looked to the contemporary world of Victorian life for inspiration. Their aim was simple: to capture their world honestly and truthfully as the artists before Raphael had done, condemning Raphael for igniting the enduring preference for classicism and idealisation in fine art.

The increasing variety of cultures and ethnic minorities was inescapable in Victorian urban centres, with many Pre-Raphaelites captivated by this new cultural diversity. Muses belonging to working-class Irish communities in London and elsewhere first caught the eyes of the artists, with portraiture of red-headed women serving as the face of Pre-Raphaelitism. The role of non-Western communities and women in their work, particularly Eaton, a Jamaican-born Pre-Raphaelite model, has only recently been examined by art historians, who have pointed to Pre-Raphaelitism’s problematic exoticisation of non-white subjects.

Over the past two years, fashion’s references to Pre-Raphaelitism have become more and more explicit. Zendaya’s Emmy 2019 look foreshadowed this trend that would firmly take hold the following year, with the actor-activists long red tresses and Vera Wang emerald gown serving as a modern-day version of Proserpine by the Pre-Raphaelite artist Dante Gabriel Rossetti, with Jane Morris as the artist’s muse. Since then, campaigns and celebrities have seized Pre-Raphaelitism, be that intentionally or unintentionally.

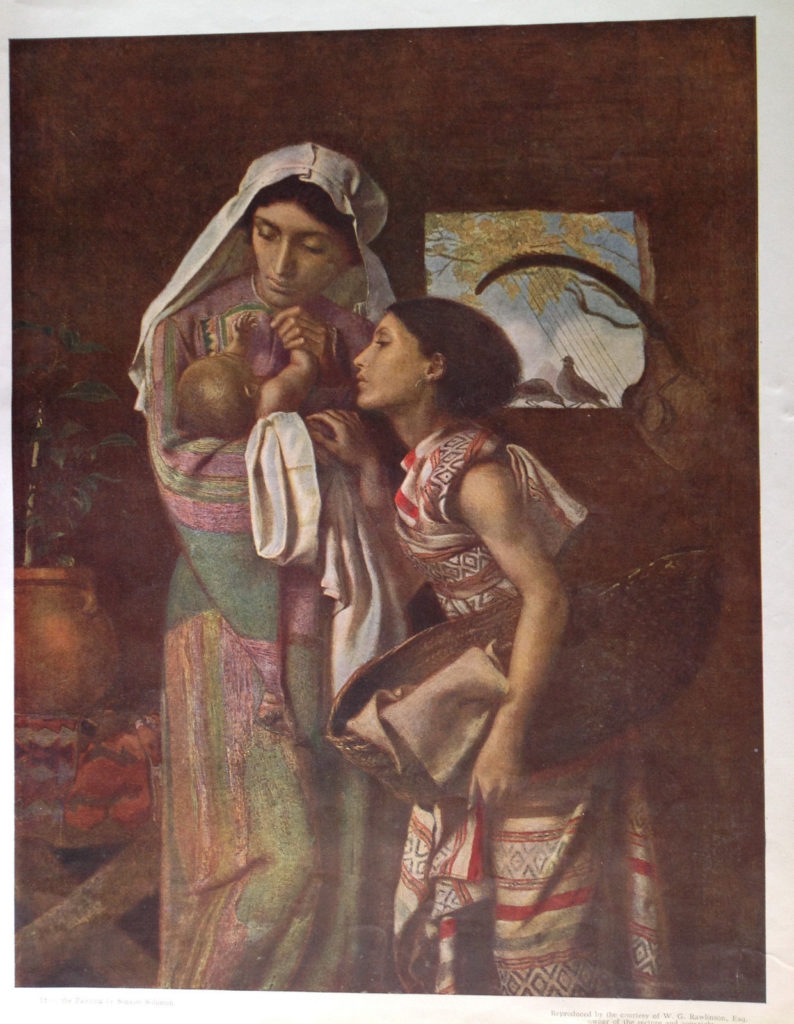

In her video ‘Otherside’ from her ground-breaking film Black Is King released in the summer of 2020, Beyoncé bears an uncanny resemblance to Eaton in Simeon Solomon’s painting The Mother of Moses, exhibited in 1860 for the first time. Paloma Elsesser’s cover story for US Vogue’s January 2021 issue, shot by Annie Leibowitz, is perhaps the climax of this trend, with Elsesser usurping Lizzie Siddal as the ultimate Ophelia from John Everett Millais’s painting of the same name, created between 1851-1852.

How does this address current concerns about racial diversity in fashion? In both her own time and contemporary scholarship on the Pre-Raphaelites, Fanny Eaton received little attention and documentation of her presence as a mixed-race model in a society entrenched in racial prejudice. It is only in the last decade that research around the model has gained traction.

Surviving artworks depicting her do not give much biographical information away either, often obscuring her facial features for aesthetic purposes. Beyoncé plays Moses’s mother in her music video, giving the figure, quite literally, the opportunity to narrate her own story. Beyoncé goes one step further to situate this story in the film’s overall exploration of black identity, giving a sense of agency not afforded to Eaton in the Victorian era.

Zendaya’s reworking of Proserpine is another example of the defiance of racial hierarchy when it comes to beauty. Morris, a favourite muse and romantic partner of Rossetti, is depicted as the ideal contemporary beauty. Zendaya is not only a model favoured by haute couture fashion houses, recently becoming the face of Valentino, but is also known as an influential voice in Hollywood, using her platform to campaign for racial equality. Elsesser’s Ophelia similarly shows a black woman replacing a pale-skinned Pre-Raphaelite beauty.

Siddal, who would later become Rossetti’s wife, is presented passively as Millais captures her at the moment of Ophelia’s death. Elsesser, a history-making “plus-size” model, is anything but passive and weak in both her US Vogue shoot and blossoming career, landing runway gigs for Fendi and Savage x Fenty among countless other impressive achievements. Assuming and reworking the protagonist of one of Tate Britain’s highlights, Elsesser, along with Beyoncé and Zendaya, creates work of the highest artistic merit while asking us to question the validity of industry beauty standards.

Considering our current climate, revisiting an artistic movement with honesty and truth at its core is perhaps to be expected. 2020 brought a plethora of challenges with it, felt in both our individual spheres and our collective space. Financial hardship and crises that required global attention such as the Black Lives Matter movement have forced us to hold up a magnifying glass to our world, with the fashion industry no

exception.

Calls for racial diversity on runways and in editorial campaigns have never been louder. In this day and age, it is, then, no surprise that fashion is harking back to and readdressing work by artists who were seen as avant-garde for the subjects they chose to present in their work. These twenty-first-century Pre-Raphaelite muses combat the patriarchal lens placed on their Victorian counterparts, ushering in a new era of women as both muses and artists in their own right.

Check out more fashion content here